This article is vital for anyone who has low back pain, and especially for anyone considering back surgery.

There has always been some controversy around lumbar spine surgery, but this has recently peaked with the interest created by the ABC Four Corners investigation.

The purpose of this article isn’t to suggest that back surgery is never a good idea, or that it is never effective.

Instead, this is a look at the back surgery controversy through the eyes of a physio who has seen plenty of patients over the years who have either:

- had good results

- wished they had never undergone surgery or

- made good recovery with non-operative treatment with a condition for which surgery is often suggested

There is a much bigger body of research in physiotherapy than when I started my career, which has helped the profession to do away with a lot of ineffective, low-value and costly treatments.

Is this the same for back surgery?

Quick Summary

Back Surgery

Click on the topic to learn more

What is the recent controversy about? – Four Corners ran an investigative report that raised a number of interesting points about back surgery and the ‘pain industry’.

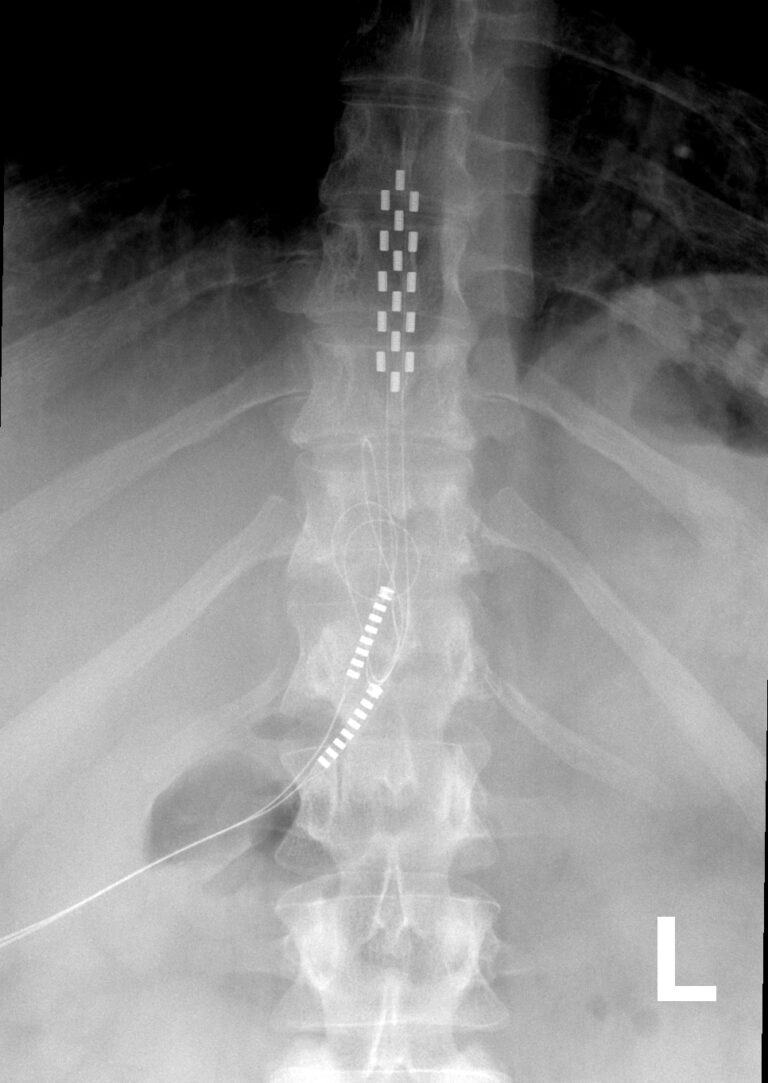

Spinal cord stimulators – Despite the cost and rising number of surgeries, the evidence for spinal cord stimulators is lacking. There are serious risks that need to be taken into account.

Lumbar spinal fusion – There has been an increase in lumbar fusion rates in Australia, despite the lack of supporting evidence for it’s use with back pain. Degenerative changes are common and are not an indication for surgery on their own.

5 important questions to consider before surgery

- What is the risk-to-benefit comparison?

- How good is the evidence?

- Is doing something better than doing nothing?

- What is the timeframe and what rehabilitation is required?

- If not surgery, then what?

Alternatives to surgery – There are evidence-based alternatives that should be explored fully before considering surgery.

How to know if surgery is for you – It is worth doing your due diligence before considering something that is irreversible.

A slightly controversional point of view – What I hope might happen next in the debate on spinal surgery.

It is no secret that there have been longstanding controversies in the use of spinal procedures for low back disorders.

Not all spine surgery is the same. There are many different procedures, each with their own rationale.

For example, there are surgeries that are a matter of emergency like treating an unstable fracture following spinal trauma or decompressing the cauda equina in cauda equina syndrome.

Back surgery has a role in alleviating back pain related to cancer, infection, and gross instability.

‘Decompressive’ spine procedures like laminectomy and discectomy are widely accepted for management of leg pain that relates to compression of nerve roots from disc hernation or extrusion, or spinal stenosis. Interestingly, the evidence base for this is not convincing, despite its widespread use (Evans et al, 2023).

Just as not all lumbar spine surgery is the same, nor is the evidence for different procedures.

This has been particularly evident since the recent program on the ABC discussing lumbar surgery practices in Australia.

My understanding as a physio of 30 years has been that back surgery can be suitable for the associated leg pain but not the back pain, except in very specific circumstances.

It seems like this adage doesn’t apply any more, but after reading this you can draw your own conclusions.

Understanding the current back surgery controversy

The recent ABC Four Corners report titled ‘Pain Factory’ focussed on the frequency, effectiveness and cost of two types of surgery for persistent (chronic) low back pain, namely spinal fusion surgery and spinal cord stimulators.

You can watch ‘Pain Factory’ here and make your own judgement about the controversy.

It took a swipe at spine surgeons of both disciplines, orthopaedic surgery and neurosurgery, plus pain physicians for the use of unnecessary surgery.

As much as I found the style of journalism quite unappealing, there were some interesting points raised that can’t be ignored.

The program criticised these procedures from three angles:

- the lack of compelling evidence of effectiveness

- the cost of these surgeries, particularly in the light of the lack of evidence

- the complication and reoperation rates

Let’s examine the procedures separately.

Spinal cord stimulators

The biggest controversy on the show was about use of spinal cord stimulators for treatment of chronic low back pain.

With a cost of surgery totalling over $50,000 AUD, and a rise in usage in Australia, you would expect there to be a mountain of quality evidence to justify it.

And that simply does not exist.

This article published by authors from University of Sydney is an interesting compilation of spinal cord stimulator evidence.

Some of the article highlights:

- A 2023 Cochrane review concluded that there may be small benefits over a short period of time but that bias, quality and small number of studies made it hard to be certain about any conclusion

- A high quality 2022 study compared spinal cord stimulators to placebo up to 6 months and found no benefit

- 520 events were reported to Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration between 2012 and 2019, with 79% reported as ‘severe’ and 13% life-threatening

- more than 80% of these reported incidents needed at least one surgery to remedy

- device malfunction was the most common adverse event at 57%

- incredibly, 4 out of 10 of spinal cord stimulators implanted are removed every year in Australia

I don’t know about you, but I couldn’t seriously consider having the surgery after reading this information.

Despite that, I know of a patient who had quite a good outcome from a spinal cord stimulator device for leg pain. She hadn’t been having success with non-surgical approaches and it was affecting her ability to work and live. At our last contact, she was still doing well.

Note, that is one person’s experience. Based on the available evidence, would I have encouraged this surgery for her? Definitely not.

Lumbar spinal fusion

Lumbar fusion is a surgery that attempts to prevent movement at one or more intervertebral levels that are thought to have ‘degenerative changes’ that are ‘causing pain’, or to manage ‘spinal instability’ like in conditions such as spondylolisthesis.

The rate of lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative changes has been gradually increasing for treatment of chronic low back pain, despite a lack of evidence of benefit from this surgery for back pain.

On the topic of surgery for degenerative low back pain the Medical Journal of Australia had this to say:

The evidence supporting spinal surgery for the treatment of LBP (low back pain) in the absence of neural compression, infection, cancer or gross instability is sparse and contrasts with the increasing frequency at which this surgery is being performed.

Evans et al (2023) Medical Journal of Australia

It is worth including in this conversation that contrary to popular opinion, you can’t use degenerative changes on magnetic resonance imaging as an indication of:

- where it hurts

- how much it hurts

- whether you need surgery

This comment from Professor Harris during the Four Corners program sums it up well:

They'll find degenerative changes and dehydrated discs and bulging discs. And so there's plenty of diagnoses. The more things you find, the more likely it is that you'll end up with somebody wanting to treat or correct that abnormality. Even though correcting that abnormality might not help the patient because it might not be associated with their pain.

Prof. Ian Harris, Orthopaedic Surgeon

To further illustrate this point, a study by Brinjikji and coworkers analysed over 3000 painfree lumbar spines examined under MRI. The rate of different ‘degenerative changes’ was categorised by age group.

This fascinating study helps to put the idea of ‘degenerative changes’ in a completely different light.

To give you an example of the results, they found

- lumbar disc degeneration in 80% of painfree 50 year olds

- lumbar disc bulge in 60% of painfree 50 year olds

- lumbar disc protrusion in 36% of painfree 50 year olds

These people are all painfree despite their ‘degenerative changes’ and don’t need surgery.

You can see what the findings were for your age group here.

On the Four Corners report, it was interesting to hear Professor Harris say that some surgeons are very unlikely to recommend lumbar fusion.

What can we conclude from that statement?

If there were clear and undeniable benefits to the surgery, there wouldn’t be any differences in opinion between surgeons. It’s a sign that the evidence isn’t strong enough.

So who’s right and who’s wrong?

Everyone thinks they are right, don’t they?

Confirmation bias is searching for, taking note of and putting more weight on the features that confirm or support your conscious or unconscious beliefs or values.

And putting less emphasis on the negative features.

We all do it!

Why does this conversation matter?

In Australia, we regularly hear that our public and private health systems are in a state of crisis.

Public health budgets are tight, which translates into longer waiting lists, stricter prioritising and ambulance ramping.

Personal budgets are tight, health insurance premiums are going up and people are questioning the value of their private health insurance cover.

More private patients are dropping out of private cover, putting more pressure back on the public system.

It makes it even more important that any procedure has solid evidence of benefit for patients, particularly when the costs are so high for both lumbar fusion and spinal cord stimulators procedures.

Despite this, surgery for back pain has increased substantially over that last decade, and disproportionately among privately insured patients.

Of course apart from the cost, there are the clinical outcomes, that is the rates of patients who are worse or at least no better.

There appears to be alarming rate of reoperation, device removal, and harms to patients who have undergone spinal cord stimulator procedures.

It is hard to see how this situation can continue without it coming to a head in one way or another.

5 important questions to consider before surgery

1. What is the risk-to-benefit comparison?

This is the most important factor in making your decision.

What is the level of risk associated with the surgery? And what specifically are these risks?

The nature of the risks and their incidence should be discussed thoroughly as part of informed consent before any surgery.

Because there is risk involved with any surgical procedure.

There may be risks to delaying surgery in particular conditions. However, in most persistent low back pain situations, there isn’t a worsening neurological condition creating urgency.

Beware that risks can be easily downplayed like ‘… but that rarely happens’ or ‘there is a small risk of that’.

Part of the decision-making process is weighing up the risks against the likelihood of benefit from the surgery.

And it shouldn’t just be about the chance of ‘better’ vs the chance of ‘worse’ from the surgery.

You need to consider the chance of ‘better’ vs the chance of ‘worse’ or ‘no change’ from the surgery.

And you need to consider just how bad the ‘worse’ could be.

Nobody tells you that paralysis means you won't feel anything. You won't feel any temperature, no hot, cold, no touch, but all you'll feel is pain. You'll lose control of your proper bowel functions. You'll lose proper bladder function, you'll lose sexual function. Those things are all gone. Where is that in the warnings? Where is that in the information provided?

Teresa Burbery - ABC Four Corners

2. How good is the evidence?

This is such an important question, but it is a minefield!

How do you find the evidence? How do you know if there is ‘cherry-picking’ of the evidence, or at the least a bit of ‘confirmation bias’?

I think it is worth doing your due diligence:

- Don’t be afraid to ask your surgeon for supporting literature

- Speak with your GP and ask their opinion

- Get a second opinion

- Do your own work online. It will generate questions to ask your surgeon

- Stay away from Facebook groups – you will usually just hear the negative stories

- Put more weight on the information from .gov.au websites.

Not all treatments have good quality trials supporting them and expert consensus does form one element of evidence-based treatment.

A lack of support in the literature isn’t so much of a concern if you are trying a new skin cream.

However, it’s more of a concern if someone is doing something potentially irreversible to your body.

3. Is doing something better than doing nothing?

It is easy to see how if someone has a lot of pain and desperate, they might have confirmation bias towards surgery as the solution if it is offered to them.

It is also easy to see how a caring surgeon might have a bias towards their treatment if they feel that they can provide a solution.

On the Four Corners program, they presented people who thought they were as bad as they could get and chose to do ‘something’.

After their surgeries, they found out how much worse things could be.

These patients and their families found out that ‘worse’ could include an increased intensity of pain, new pains, paraplegia, shocks, burns and death.

Each of them would gladly have turned back time and not had the procedure done.

Doing ‘something’ isn’t always best.

However, doing nothing can carry risks too.

The risks of not taking any action can be:

- continued pain

- ongoing analgesia requirements

- social effects

- mental health effects

- reduced quality of life

- effects on cardiovascular health

and so much more.

4. What is the timeframe of recovery, and what rehabilitation is involved?

This information is really important so the patient has reasonable expectations.

- How long should it take to feel a benefit from the surgery?

- How long until you have fully recovered?

- Are there going to be any ongoing restrictions on what you can do?

Depending on the type of surgery, there are often time and financial commitments to rehabilitation that you’ll need to make afterwards to ensure a full recovery.

5. If not surgery, then what?

I think answering this important question was a big missed opportunity on the the Four Corners program.

They were able to identify that certain surgeries are quite expensive and not supported by evidence.

But if I were a back pain sufferer considering surgery, I would have been left thinking ‘so what should I do then?’

There was no discussion of the effective, evidence-based alternatives that exist and how Australian researchers are leading the way with research into non-surgical approaches to helping low back pain.

Focus on first understanding that chronic back pain is not a simple problem, which is why it does not have a simple solution, and then on slowly reducing pain system sensitivity while increasing your function and participation in meaningful activities.

Prof Lorimer Moseley

What are the alternatives to surgery?

As we learn more about the complexity of pain and how it works, the variable results for surgery and other ‘biomedical’ treatments become less surprising.

We now know pain is an incredibly complex process and its purpose isn’t to provide a simple read-out of tissue condition or damage.

It is completely unrealistic to expect a purely physical intervention that is to ‘cut something out’, ‘fuse something together’ or ‘provide an alternative input’ to be the solution to a multi-system, multi-dimensional problem like pain.

However, there are good alternatives for patients with chronic low back pain that do address pain in a multi-dimensional way.

Understanding the idea that back pain is more than just about the back is a critical step in the successful non-surgical management of back pain.

Chronic low back pain should be managed with a holistic biopsychosocial approach of generally non‐surgical measures.

Evans et al (2023) Medical Journal of Australia

Evidence for non-surgical management

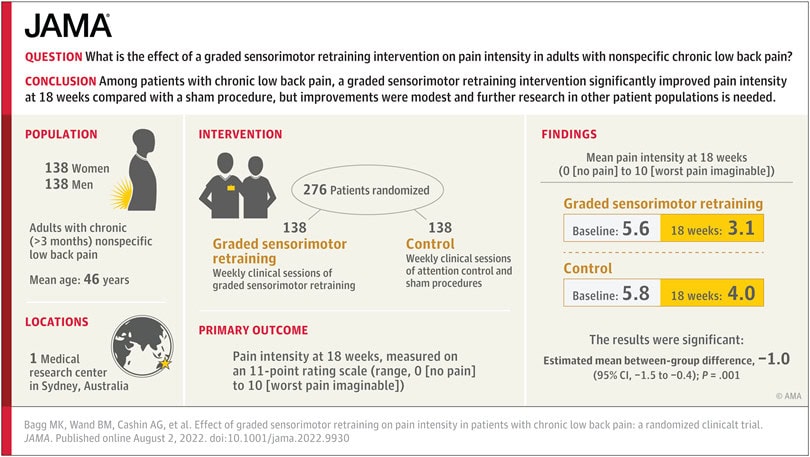

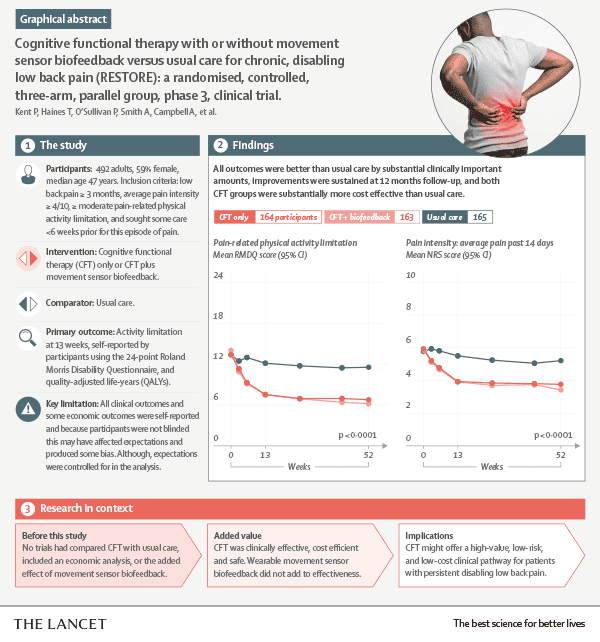

The RESOLVE trial published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and the RESTORE trial published in the Lancet have lead the way with recent evidence for effective non-surgical solutions for low back pain..

The RESOLVE trial (with a pictorial representation of the abstract shown above) and the RESTORE trial (with its abstract shown below) have similar names and similar goals but came from two different groups of researchers. It seems like they didn’t really consult each other with the naming!

Regardless, both trials were important steps in validating treatment of low back pain and leg pain that a surgery will never be able to address.

Our approach to helping persistent low back pain is based on these principles of combining knowledge, brain retraining, movement and strengthening using the Fit For Purpose Model.

An additional tool is the use of Virtual Reality of the type developed by Reality Health which allows for even greater learning opportunities.

We have been impressed with the way that patients engage with the VR technology, how it leverages the pain education and allows them to move in ways that they hadn’t thought possible.

How can you know if back surgery is right for you?

If you are looking at surgery, and particularly if you have chronic pain, I would be weighing up all your options very carefully.

Your research should not only include your specialist’s opinion. I would argue strongly for getting a second surgical opinion, and the opinion of your trusted GP.

I would also talk to an up-to-date physio to see what the viable alternatives to surgery are.

I don’t think you can rely on the opinion of one person who (consciously or unconsciously) has a vested interest in the procedure.

This is your body after all, and you can’t have your time all over again.

The back surgeon's responsibility (in my opinion)

I feel like it is incumbent on the back surgeon to be fully versed in the current non-surgical options that are available. They should be the expert on surgical and non-surgical options, not just with a glancing knowledge of what physio can provide.

It is also incumbent on the back surgeon to know exactly what the patient has done before offering some kind of surgical intervention.

This knowledge needs to be to a greater depth than ‘they have done physio and it didn’t help’.

If they have done 6 months of dry needling or electrotherapy 3 times a week, then it shouldn’t be a surprise that it hasn’t helped.

What's next in the back surgery debate?

There was review into alternative therapies a few years ago to weed out the ineffective therapies that were contributing to increased private health insurance costs.

It would seem reasonable to have a similar review of evidence for the use of spinal procedures.

However, I just can’t see that happening.

Hopefully, there will be more quality randomised controlled trials to demonstrate effectiveness of surgery versus conservative treatment, and not just one procedure versus another.

I imagine people like Professor Ian Harris will continue to be criticised from within his profession, but personally I think it is great that someone ‘on the inside’ has the strength to question what is happening and to call out faulty logic.

In the meantime, we will continue to advocate for exploring non-surgical solutions first as per all the medical guidelines for managing chronic low back pain.

References

https://theconversation.com/evidence-doesnt-support-spinal-cord-stimulators-for-chronic-back-pain-and-they-could-cause-harm-227358

Jones CMP, Shaheed CA, Ferreira G, et al. Spinal Cord Stimulators: An Analysis of the Adverse Events Reported to the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration. J Patient Saf. 2022 Aug 1;18(5):507-511. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000971.

Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015 Apr;36(4):811-6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4173.

Lachlan Evans, Thomas O’Donohoe, Andrew Morokoff and Katharine Drummond. The role of spinal surgery in the treatment of low back pain. Med J Aust 2023; 218 (1): 40-45. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51788

Bagg MK, Wand BM, Cashin AG, et al. Effect of Graded Sensorimotor Retraining on Pain Intensity in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;328(5):430439. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.9930

Kent P, Haines T, O’Sullivan P, Smith A et al. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial. Lancet. 2023 Jun 3;401(10391):1866-1877. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00441-5. Epub 2023 May 2.

Would you like to speak with one of our back pain physios FREE OF CHARGE?

What’s holding you back? Let’s talk about it!

BOOK ONLINE or call us on (08) 7282 0871 and let’s lock in a time!

NB: This offer is for Adelaide residents only.

Frequently-Asked Questions

When is back surgery a good idea?

Back surgery has a role in cancer, infection, gross instability, unstable fracture and acute spinal cord or cauda equina decompression. There is a reasonable case for surgery in sustained or worsening neurological loss from compression of a nerve root.

The evidence for spinal surgery for solely for back pain is weak and more controversial.

How long does it take to recover from back surgery?

The answer to this will vary depending on the type of back surgery. Recovery from a microdiscectomy is different from a lumbar fusion. There is a good chance that you will feel stiff and sore at the least for 4 to 6 weeks.

For most surgeries, you can expect that it will take between 6 to 12 months to be at your best.

What is the most common back surgery?

Decompression and stabilisation surgeries are the most common back surgeries. Decompression includes laminectomy and discectomy. Spinal fusion is a stabilisation procedure, which can be achieved in a variety of ways.